Africa's Toxic Lake - Lake Nyos

Image of Lake Nyos. Source: Department of Geological Sciences, San Diego State University.

9:30PM, August 12, 1986... a cloudy mix of CO2 and water droplets rose violently from Lake Nyos in Cameroon. A 50-m gas cloud rushed down at 100 km/hr and swept through the valleys over a distance of 23 km, killing more than 1,700 people, 3,000 cattle, and numerous birds and animals. So what happened? The locals thought it was the wrath of a spirit woman from local folklore that lives in lakes and rivers. Scientists were asking different questions... why was this event so sudden? Why was this event so tragic?

The Geologic Story of Lake Nyos

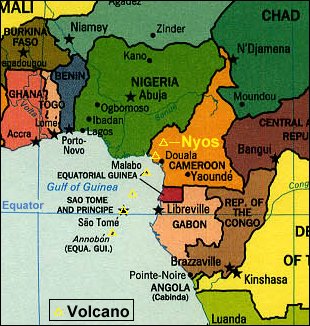

Map of the Cameroon Volcanic Line. Source: Steve Earle, Malaspina University College.

Lake Nyos is one of about thirty similar crater lakes that lie along the Cameroon Volcanic Line in western Cameroon. It occupies a feature called a maar crater which formed from a hydrovolcanic eruption about 400 years ago. The lake is 200 meters deep and 1.5 km2 in area. The region receives 2.5 meters of rain per year. Once the lake fills, the excess water spills out the lake and down the flanks of the dormant volcano.

Two years before the 1986 Lake Nyos 'eruption,' a similiar event occurred at Lake Monoun, located 60 miles to the southeast. A heavy cloud of toxic gas also appeared at this location and killed 37 people. Both of these lakes were the only ones in the world with significantly high CO2 levels in the water. Scientists began to question where the CO2 was coming from, and why were the lakes erupting CO2 gas.

Studies shows a hot magma chamber 50 miles below Lake Nyos (remember, it is in the crater of a volcano). The magma releases CO2 and other gases that get trapped in the cold bottom lake waters. Now the amount of gas that can be held in water depends on pressure and temperature—the greater the pressure, the more gas can be trapped. However, there is a limit! Once the 100% saturation level is reached and surpassed, a foaming column of carbonated water shoots up from the bottom and erupts. By itself, the erupting gas cloud is not dangerous. But to humans and animals, it can be lethal. CO2 is heavier than normal air, which is why it rushes down the flanks of the volcano. The air that we breathe typically contains 0.03% CO2, and it only takes a level of 10% to be fatal.

Degassing the Lake

Image of Lake Nyos. Source:Science in Africa.

It doesn't take long for the gas concentrations to build back up in the lakes. Lake Nyos is already 60% saturation, and Lake Monoun is at 83% CO2 saturation. Before the lakes erupt again, an international team of scientists funded by the U.S. Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance, the French Embassy, and Cameroonian government, are working to vent the gas from the lake bottom to the surface. Pipes that are 5 inches in diameter are being anchored to floating platforms and lowered to the deepest depths of both lakes to allow for the CO2 cloud to vent. Unfortunately, the CO2 levels build up faster than they are being released, so the scientists have their work cut out for them.

More pipes need to be inserted to make sure that an explosive eruption doesn't happen again. But now there is a new concern—a new lake with a thousand times more gas than Lake Nyos. Located on the Rwanda/Democratic Republic of Congo border, Lake Kivu has not only CO2 but one-fifth of the gas content is methane. A company has moved to see if it is possible to exact the methane from Lake Kivu to try to revitalize the economy of the region. It is an interesting project with great potential—read about the methane project for yourself!