A 19th Century Improvement - Burton and Speke

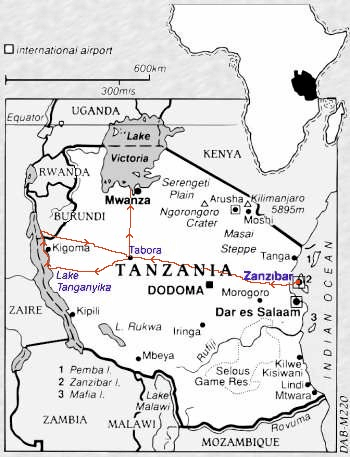

Burton and Speke, 1857-1858. Source: http://perso.wanadoo.es/antarctica/Mapas%20zona%20NIlo.htm

Nothing much happened to improve our understanding of the Nile floods until the 19th century. We owe much of our awareness of global geography to one man: Richard Burton (1821-1890). He was a truly remarkable character, and it is worth spending a little time learning about his life. Burton was born in England, pursued a career in the Foreign Service, and was one of the world's leading explorers and adventurers. He was both brilliant and charismatic, but an extremely difficult person to work with (and more difficult yet to supervise). He was an intelligence agent in India in the 1840s, where he proved himself a remarkable linguist and anthropologist, with a penchant for erotica that ultimately nearly ruined him and his wife. His translations of the Kama Sutra, The Perfumed Garden, and The Arabian Nights are famous. He brought erotica of the orient to the west.

By the end of his life, Burton was fluent in 29 languages, most of them from remote regions of the world. He never needed a translator, but rather mastered the necessary languages and dialects to communicate with the local people.

In the 1850s, Burton disguised himself as a pilgrim and entered the Holy Cities of Mecca and Medina--the first European to do so and survive (rumor has it that an earlier adventurer tried the same stunt and failed because he was revealed to not be circumcised). He was also the first European to enter the Forbidden City of Harar in Somalia, where he feigned interest in opening up a trade route. He contracted syphilis during this time, a disease which ultimately weakened him on his later African explorations and probably led to his failure to be credited as the one who discovered the source of the Nile.

In 1857 he convinced the Royal Geographical Society that he should be funded to search for the source of the Nile. This quest was not only one of geographical curiosity. There was also tremendous concern about the slave trade, and the goal of replacing traffic in humans with trading routes for other goods. Burton teamed up with John Henning Speke, an adventurer and experienced game hunter, although the two men had little respect for one another. Burton regarded Speke as a naive and timid man only interested in hunting animals for sport; Speke viewed Burton as an arrogant, stubborn man incapable of responsible planning. Both were largely correct.

Burton and Speke traveled to Zanzibar and from there mounted an expedition inland.

These passages give a flavor of the traveling party:

There was a rough and ready order in the long procession when it finally got under way. In the lead went the guide, wearing a ceremonial head-dress and carrying the red flag of the Sultan of Zanzibar, and behind him marched the drummer. The cloth and bead porters came next with their bolster-like bundles on their heads, then the men carrying the camp equipment, and their women, children and cattle. The armed guard [askaris] was dispersed along the line, each man carrying a muzzle-loaded ‘Tower musket’, a German cavalry saber, a small leather box strapped to the waist and a large cow-horn filled with ammunition. Many of them were accompanied by their women and personal slaves … Almost every male member of the expedition had a weapon of some kind together with an assortment of pots and pans and a three-legged wooden stool strapped to his back. A continuous and violent uproar of chanting, singing … and shouting accompanied the march, for it was thought important to make as much noise as possible so as to impress the local tribes. If a hare chanced to run across the track all downed burdens at once to go in pursuit of the animal which, if caught, was eaten raw.

—From A Rage to Live, and cited therein from Moorehead, Alan, The White Nile by Alan Moorehead, Penguin, 1963, page 42.I lay for a fortnight upon the earth too blind to read or write, too weak to ride, too ill to converse. Jack was almost as groggy on his legs as I was, suffering from a painful ophthalmia, and a curious contortion of the face, which made him chew sideways, like an animal that chews the cud.

—From A Rage to Live, p. 270, and cited therein from The Life of Captain Sir Richard F. Burton by Isabel Burton, Vol. 1, p. 300As Speke was the healthier more quickly, he was dispatched to cross Lake Tanganyika. He was barely healthy, unable to speak the language, and not very good at organizing men. Worse yet, he faced a terrible storm on the lake and nearly lost all of his supplies. Having reached the far shore in a storm, the group was attacked by small beetles, one of which burrowed into his ear:

[passage page 272-273 from A Rage to Live]At night a violent storm of rain and wind beat on my tent with such fury that its nether parts were torn away from the pegs … on the wind’s abating, a candle was lighted to rearrange the kit, and in a moment, as if by magic, the whole interior became covered with a host of small black beetles, evidently attracted to the glimmer of the candle.

Speke spent some time trying to clear the insects out of his clothes and equipment but in the end gave up, extinguished his candle and settled down to sleep despite the annoyance of the ‘intruders crawling up my sleeves and into my hair, or down my back and legs’. Some time later he was awakened by an intense irritation as one of the beetles crawled into his ear. Nothing he did dislodged the tiny creature; shaking and banging his head only served to make it burrow deeper until eventually it came up against the ear-drum. ‘This impediment evidently enraged him, for he began with an exceeding vigour, like a rabbit at a hole, to dig violently away at my tympanum. The queer sensation this amusing measure excited in me is past description.’ Seeing Speke’s excusable panic, his escort made several suggestions including blowing tobacco smoke into the ear and the application of hot oil or salt. Unfortunately none of these commodities was available.

I therefore tried melted butter; that failing, I applied the point of my penknife to his back, which did more harm than good for though a few thrusts quieted him, the point also wounded my ear so badly that inflammation set in, severe supporation took place, and all the facial glands extending from that point down to the point of the shoulder became contorted and drawn aside, and a string of boils decorated the whole length of that region. It was the most painful thing I ever remembered to have endured, but more annoying still, I could not masticate for several days and had to feed on broth alone. For many months the tumor made me almost deaf and ate a hole between the ear and the nose, so that when I blew it, my ear whistled so audibly that those who heard it laughed. Six or seven months after this accident happened, a bit of the beetle—a leg, a wing, or parts of its body—came away in the wax.

—From Speke, J.H. What Led to the Discovery of the Source of the Nile (1864). Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons (pages 324-325); intervening text is from A Rage to Live.

Speke did in fact find the source of the Nile. He knew it, but did not take the steps necessary to prove his claim and therefore never fully received credit for the discovery. His maps were poorly drawn, and he never convinced Burton of his findings.

Burton and Speke returned to England as bitter enemies. Speke promised Burton that he would keep quiet about his discovery so that they could present it together at a meeting of the Royal Geographical Society. He failed to keep that promise, and told everyone that the Nile was conquered and that he had done it alone.

Burton was furious. He had gotten the funding, he had organized the men, he had done most of the work, and Speke's maps were terrible. Speke did follow through with his work, though, and returned to the area two years later with an old explorer friend James A. Grant to substantiate the earlier finding. Still Burton did not believe his claims.

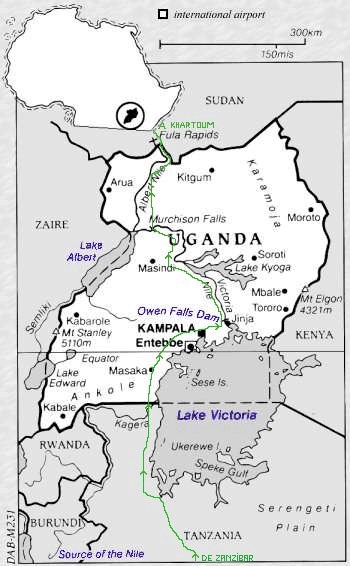

Speke and Grant, 1861-1862. Source: http://perso.wanadoo.es/antarctica/Mapas%20zona%20NIlo.htm

In 1864, a public debate was organized by the Royal Geographical Society to settle the score between the two men. There was an immense amount of political activity associated with the debate: who would be given a fellowship, who might be knighted, who was correct? Each man had strong supporters and detractors among the crowd of several thousand expected to attend the debate.

Burton was clearly the better public speaker, and Speke knew his maps would never stand up to public scrutiny. The debate, however, never took place. Speke died in a freak hunting accident just hours before it was to start. Eye witness accounts are inconsistent, but Speke was such an accomplished hunter that one concludes he killed himself rather than face Burton's ridicule in public. Ironically, Speke was correct about the source of the Nile.

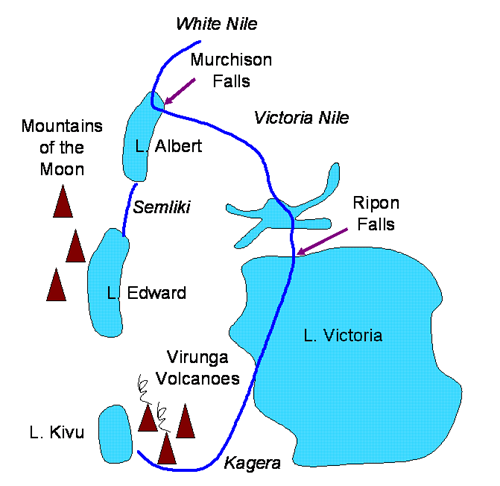

The sketch map below shows the complexities surrounding the identification of the source of the Nile. Remember that Burton and Speke were searching for the source of the White Nile. As this river runs farther south than the Blue Nile, the equatorial rift lakes that feed the White Nile are correctly termed the Headwaters of the Nile. In fairness, however, we must acknowledge Lake Tana in Ethiopia as the source of the Blue Nile.

Sketch map of the two sources of the White Nile. It is easy to see why so many explorers were certain that each one had found THE source of the Nile. Source: Dr. Tanya Furman.