Introduction

The East African Rift is one of the largest physiographic features on the planet. In this unit we will look at the geology and climatic history of this enormous fault-bounded valley that splits the continent of Africa in two. In this unit you will explore the volcanic and earthquake activity that characterizes the East African Rift. You will also take a detailed look at the sediments the lie within the Rift lakes, in order to learn about ancient climates in this region.

Map of East Africa showing some of the historically active volcanoes (red triangles) and the Afar Triangle (shaded, center) where three plates are pulling away from one another: the Arabian Plate, and the two parts of the African Plate (the Nubian and the Somalian) splitting along the East African Rift. Source: USGS.

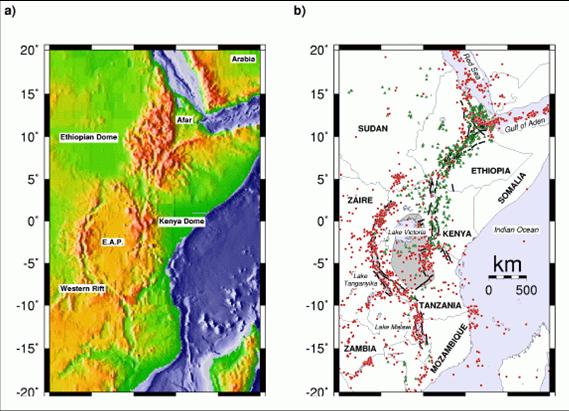

The topography of the Rift may surprise you: the left-hand side of the image below (a) shows the topography of Africa. The Rift is a complex slice along a large zone of high land, much of it at elevations over 6000 feet above sea level. Impressive though it is, the Rift is just the surface evidence of processes occurring at great depth within the Earth beneath Africa. If we were to look inside the Earth, we would see a huge body of unusually warm material flowing slowly upward from the core-mantle boundary towards the surface of the planet. This material pushes Africa upwards, forming the blister-like regions of high topography that we see, until the surface cannot stretch any farther and cracks apart. These deep cracks are the East African Rift System, stretching over 3000 km from the Afar triangle at the southern end of the Red Sea southward to Mozambique.

Source: R. Keller, University of Texas at El Paso.

The Rift is a region of tectonic activity, which means that there are abundant earthquakes and volcanoes along its entire length. In the right-hand image above (b), the green dots represent active volcanoes and the red dots show the location of earthquakes along the Rift. It is along these volcanically-active faults that a new ocean basin will one day be formed, as Africa slowly splits into a large continent (now on the west side of the Rift) and a small continental fragment (the land to the east of the Rift). This process will take dozens of millions of years, but we can go there today to see how it happens.

The faults that form the borders of the Rift are immense. They often extend as much as two kilometers above the valley floor, and continue downward for as much as 40 km. Where the faults are young, as in central Ethiopia, they are easily visible and lack vegetation.

Fault along main Ethiopian rift. Arrow denotes about 700 meters of vertical displacement along a fault.

Source: From the personal collection of Dr. Tanya Furman.

Older fault scarps like those in southwestern Tanzania may be covered with plants or heavily eroded and therefore harder to see clearly.

Fault scarp in southwestern Tanzania. Source: From the personal collection of Dr. Tanya Furman.

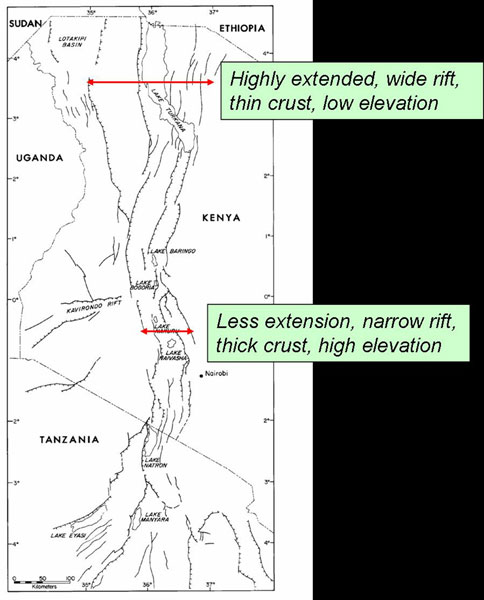

At its widest point–the Turkana Depression in northern Kenya–the African Rift is about 150 km across. More typically–as in central Kenya–it is between 30 and 50 km wide.

Map showing the Turkana Depression in northern Kenya. Source: From the personal collection of Dr. Tanya Furman.

Remember that we discussed earlier the evidence of our early ancestors that has been found in the Rift valley. The steep walls of the Rift itself likely contributed to our development, as well as that of many other species (see image left, below).

Camels and Topi. Source: From the personal collection of Dr. Tanya Furman.

Chimpanzees and gorillas live only in forested regions to the west of the Rift, in habitat that suits their physical make-up. In contrast, ancient hominids probably developed in the grasslands of the Rift floor where their growing ability to walk upright made it easier for them to look for food, spot predators and reduce the effects of the hot sun on their bodies. Interestingly, the Rift walls are still a formidable barrier to animal mobility. Most of the large and small mammals found in the eastern portion of the Rift (herbivores and carnivores) are not found in the western rift. Even bird species are commonly restricted to one valley or the other, and rarely cross from one side to the other. The topi shown above (left) are common in the Western Rift, but are almost unknown in the Eastern portion. (Topi are medium-sized antelopes with a striking reddish-brown to purplish-red coat.)