Volcanoes of the Rift

Now let’s return to our discussion of the volcanoes that line the African Rift. Remember that these volcanoes are simply “safety valves” through which the earth releases excess heat from its deep interior. The African Rift volcanoes bring us important information about the rifting process, telling us how thick the continent is (how far rifting has progressed) and what materials it is made of. Since we cannot go visit the continental interior ourselves, we rely on volcanic rocks to bring is this information.

You are probably familiar with one or more of the African volcanoes already. Mounts Kenya and Kilimanjaro are both major volcanic mountains, although neither one is active at present.

Mount Kenya. Source: From the personal collection of Dr. Tanya Furman.

Mount Kilimanjaro. Source: From the personal collection of Dr. Tanya Furman.

Another famous volcano in Tanzania is Ol Doinyo Lengai, which erupts a very unusual type of lava called carbonatite. There is no other volcano on the Earth that has lava of this composition.

We tend to think of volcanoes as dangerous, but throughout the Rift volcanoes usually are more beneficial than harmful. Their ash tends to be rich in phosphorous, making for fertile soils that are suitable for agriculture. In Rwanda, for example, farmers can grow three crops each year on the fertile soils of the Virunga volcanoes. In the slide show below, notice how the steep volcanic slopes are cultivated meticulously, all the way to the top! Farther south in Tanzania (slide show image 3), there is less rain but the fertile soils are still heavily cultivated. Notice how much drier the climate appears in this photo than in the previous one.

Some of the Rift volcanoes have deep craters at their peaks, the result of explosive eruptions (the same eruptions that spread ash across the region). These craters often develop lakes that provide the population with much-needed drinking water. Ngozi crater in Tanzania is also known for the healing power of its waters—most likely the result of warm, sulfur-rich inputs from the active volcano itself. In some areas, hotsprings are common as well, reminding us of the power of the volcanoes below.

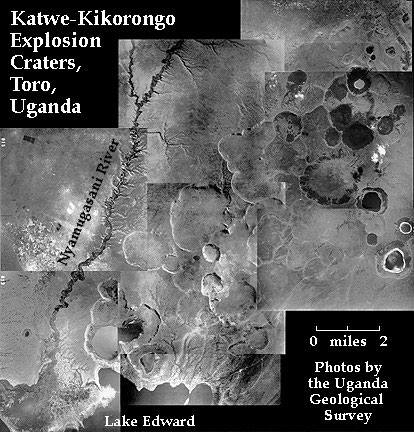

A few Rift volcanoes erupt material from over 100 km (60 miles) below the surface. How do we know that? This area in the Toro-Ankole volcanic region in Uganda is pock-marked with explosion craters, some of which contain small diamonds! We know that diamonds require tremendous pressure to grow, and so their presence in this part of the Rift tells us just how thick the continent still is, as well as what it is made of at depth.

Katwe-Kikorongo Explosion Craters. Source: Uganda Geological Survey.