Earthquake!

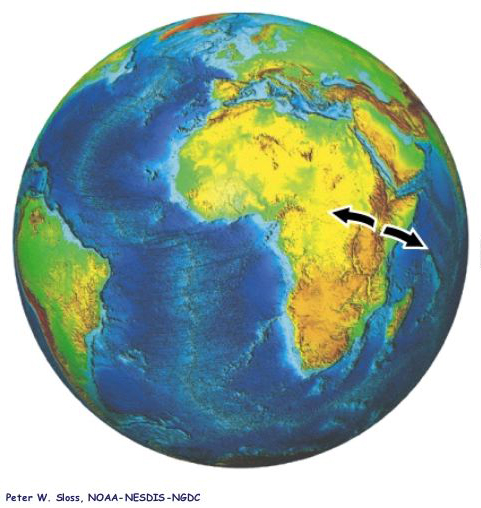

The most recent significant seismic event (earthquake) to hit the East African Rift System occurred on December 5 th, 2005. The event occurred at a depth of 22 km below the surface and was located along the border between Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, about halfway between Burundi and Zambia. Find this location on a map of Africa. Where did the earthquake take place? Does it surprise you that earthquakes can occur beneath huge bodies of water like Lake Tanganyika?

Location of the epicenter. Source: USGS.

Want to see more? Google Local has a nice satellite image of the epicenter.

Lake Tanganyika–like all of the other African Rift lakes except for Lake Victoria–lies in a graben (a down-dropped block of land bounded by extensional, or normal, faults) along the axis of the great rift. Lake Tanganyika is so deep that it contains over one-third of all the fresh water on the planet. The lake is almost a mile deep and has no outlets via rivers that might link it to other lakes. Remember that Burton sent Speke across the lake in a terrible storm to search in vain for the river they were certain must lead northward to the Nile. Thanks to the lake’s great age, depth, and geographical isolation, Tanganyika is populated by an enormous number of species of mollusks and fish that are not found anywhere else in the world. Of the 214 species of fish known from Lake Tanganyika, 176 are endemic to the lake.

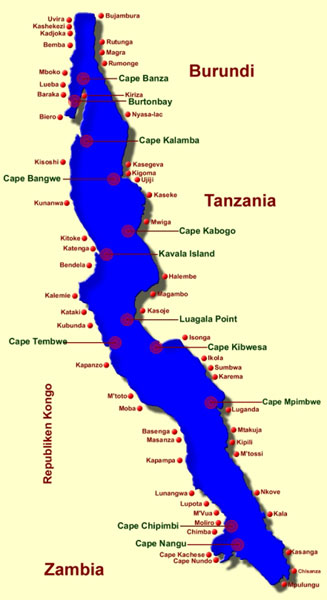

Map of Lake Tanganyika. Lake Tanganyika is 670 km long and up to 1470 meters deep. It forms the border between Burundi and Tanzania to the east and Zambia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the west. Notice the label for Burtonbay in the northern part of the lake - named by John Speke in honor of Richard Burton. Source: Duboisi.com.

But back to that earthquake… The December 2005 event measured 6.8 on the Richter scale, making it similar to the Northridge earthquake of 1994. At least 6 people were killed, and over 300 homes and a church collapsed in eastern Congo. The event was felt throughout the region, over distances up to 1000 km away. It was followed over the next 10 days by over half a dozen smaller aftershocks with Richter magnitudes up to 5.4–enough to be felt, but not strong enough to cause damage to structures (and all susceptible houses had fallen down already by then).

Earthquakes are an important feature of the Rift Valley. Think back to the second week of this course, where we used the locations of earthquakes to define boundaries between the lithospheric plates that form the surface of the earth. The Lake Tanganyika event was just one of many along the Rift Valley, defining this feature as a plate boundary.

Source: USGS.

A plate boundary? In the middle of Africa?

The continent of Africa is in the midst of the very slow process of rifting – gradually pulling into two pieces that will be separated by new ocean floor.

Inception of rifting along the East African Rift System. Source: Department of Geological Sciences, Florida State University.

To the north, both the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden are young oceans that formed through the separation of Arabia from Africa over the past 25 million years. Now imagine yourself 25 million years in the future, looking at a map of Africa and the Middle East. The Red Sea and Gulf of Aden will each be about twice as wide as they are now, and a new narrow ocean may have formed at the head of the Afar triangle along the northern Rift Valley. In another 100 million years, the eastern horn of Africa may be its own skinny continent!

Rifting is hard work, because the whole lithospheric plate (over 100 km thick) needs to be torn apart. Earthquakes tell us about that process. Their energy comes from the breaking of rocks beneath the surface of the earth. In the case of the December 2005 event, the rocks broke at a depth of 22 km–in the top quarter of the lithosphere. The walls of Lake Tanganyika formed through the combined efforts of thousands of earthquakes, each moving the lake floor downward by perhaps tens of centimeters. That is a lot of earthquakes, and there will need to be many more before Africa is able to rift into two pieces. In the next few pages, we’ll take a look at the geology of the rift in more detail.