The Nile Delta

What is a delta? We know that the Nile delta gave its shape to the Greek letter Δ, but the Nile is not the only river in the world that has such an elegant delta. To geologist, "delta" is the name given a body of sediment deposited at the mouth of a river where it flows into a standing body of water. Deltas form through a very simple process: fast-moving water can carry lots of sediment (sand, clay, mud and even rocks) but these heavy particles settle to the bottom rapidly when the water stops flowing. As rivers enter the sea, or even a large lake, the river velocity slows down markedly, and the sediment that was traveling downstream stops moving and falls to the bottom.

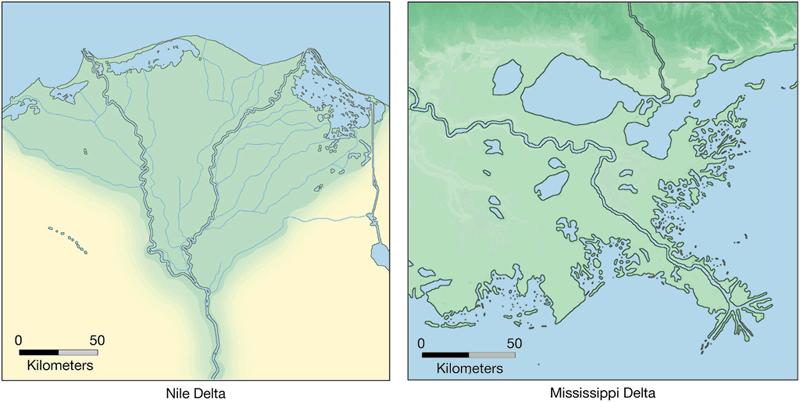

The eventual shape of a delta is formed by the action of waves, tides and the stream itself. When the river is large, it can carry a lot of sediment and thereby form a large delta. In such cases the main flow splits into two or more distributaries, smaller streams that traverse the growing delta. We see this pattern in the Nile as well as in our own Mississippi River delta. In fact, the Nile and Mississippi deltas are very similar in size and shape.

Images of the Nile Delta (left) and Mississippi Delta (right). Source: Copyright 2002 Tasa Graphic Arts, Inc.

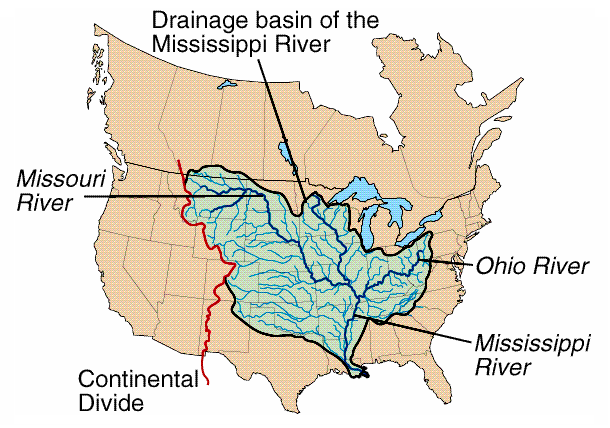

Let's take a moment to talk about how deltas form and grow. Like the Nile, the Mississippi River carries a tremendous amount of sediment. Why? These rivers drain huge tracts of land - dirt from the majority of the US is carried by the rain into the river and down the Mississippi River towards the Gulf of Mexico.

Drainage Basin of the Mississippi River. Source: Plummer/McGeary/Carlson Physical Geology, 8th edition, Copyright 1999, McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

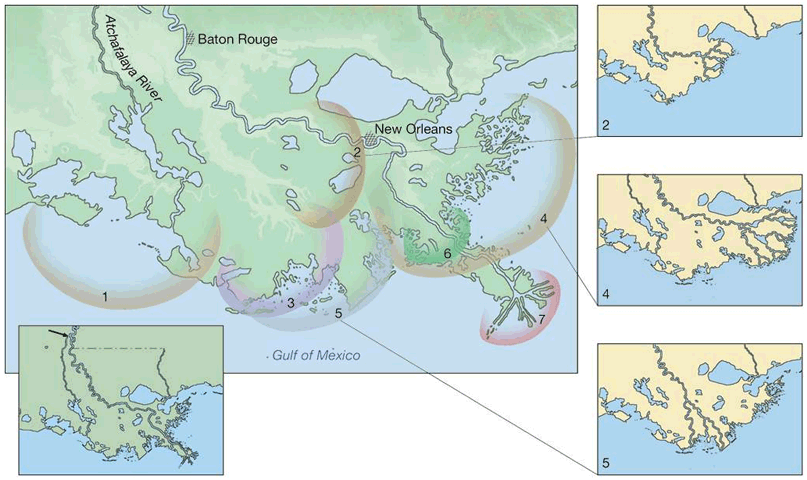

One big difference between the two is that while the Nile delta is shrinking (the Mediterranean Sea is eating away more sediment than the river can supply), the Mississippi delta is growing. The image below shows the growth of the Mississippi delta over the past 10,000 years. Each of the numbered, colored lobes represents a portion of the delta that grew for a period - until the pile of sediment grew too large and the river needed to find a new course. Look closely at lobe 1, where the Atchafalaya River runs into the Gulf of Mexico. The Mississippi River would like to flow through this distributary, but the powers of commerce and control maintain the current river channel. The cost of this effort is tremendous, and as the effects of Hurricane Katrina have shown, maintaining a river with levees is not always easy.

Mississippi River delta growth over time. Source: Copyright 2002 Tasa Graphic Arts, Inc.

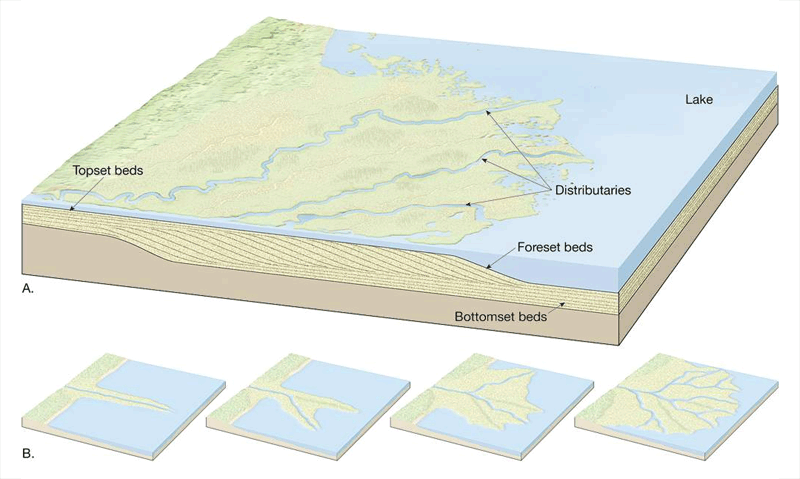

What does a delta look like inside? The image below shows a cut-away view of a growing delta. As the delta pushes out into the sea, or progrades, successive pulses of sand-sized sediment create the tilted foreset beds, while the smaller particles (which travel farthest) form the horizontal bottomset beds. As the sediment pile grows, the river distributaries must change course (remember, they cannot flow uphill) and in so doing generate new lobes for the delta.

Cut-away view of a growing delta Source: Copyright 2002 Tasa Graphic Arts, Inc.

Note: Please click on the image to see a larger version.

As a result, the delta itself is an environment of physical change. Over human time scales, one can expect the location and flow regime of distributaries to change as the sediments thicken. Deltas are also subject to severe erosion and flooding by unusually high tides and storms. Worse yet, delta soils dewater and compact over time causing the ground level to sink relative to sea level. Extensive construction and pumping of groundwater for domestic or industrial use both compound this problem, and as a result the major delta cities of the globe are in trouble. New Orleans, Venice, Shanghai, and Bangkok are all examples of delta cities that are losing the long-term battle between land and sea.

What about the Nile delta? We look next at examples of ancient cities built upon the Nile delta that have vanished from view entirely: Heralkeion, Menouthis and Eastern Canopus. We know a lot about these cities from the legends and myths of the ancient Greeks, but it wasn't until 1999-2000 that a group of French marine archaeologists found well-preserved evidence of them on the floor of the Mediterranean Sea.

Herakleion and Canopus were built at the mouth of the Nile, along the outlets of the Canoptic distributary of the Nile. They were established as centers for commerce and navigation, and were the primary gateways to the Nile and all of Egypt from the 1st through 6th centuries AD. All ship traffic entering the Nile River from the Mediterranean paid taxes in Herakleion. To the east, the town of Menouthis - likely a part of the larger city of Canopus - was the site of a temple to the goddess Isis, and became a destination for religious pilgrims as well as extravagant religious festivals.

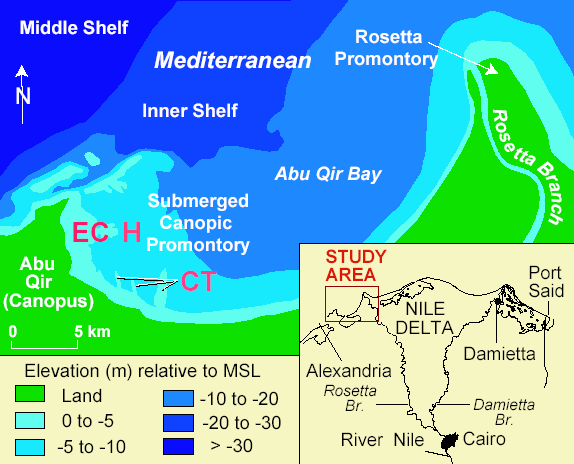

Canopus distributary Source: Submergence of Ancient Greek Cities Off Egypt's Nile Delta — A Cautionary Tale

Although the cities had easy access to fresh water and the Mediterranean Sea, they were unprotected against the effects of flooding, earthquakes and ground subsidence. Both of these cities now lie submerged to a depth of 5-7 meters beneath the waters of Abu Qir Bay. It is likely that some combination of these natural phenomena was responsible for their rapid demise more than 1200 years ago.

Geologists and archaeologists have reconstructed a scenario of disaster rather than one of gradual subsidence of the cities. Remains found under the Mediterranean indicate that Menouthis was abandoned rapidly, apparently in response to liquefaction of the silt-rich delta sediments. What is less clear is the cause of the sudden transformation of the ground into muddy liquid. One interpretation is that a powerful earthquake shook the area. A second interpretation is that one or more unusually strong Nile floods caused the damage.

The date of the destruction is reasonably well-constrained. Arabic coins found at the site date from 724 and 740 AD, indicating the cities were functioning centers of trade at that time. Canopus is also mentioned in contemporary writings by travelers of that same era. Previous work in the Middle East documented a strong (magnitude 7.0 to 7.3) earthquake along the Dead Sea transform fault in 749 A.D. that affected large portions of the region (can you locate the Dead Sea transform?). As residents of San Francisco know all too well, soil liquefaction is both common and treacherous during an earthquake and could easily account for the soil failures observed in the ancient delta. Archaeological investigations have found temple columns aligned parallel to one another under the water, a configuration often associated with earthquake damage. Written records also indicate anomalously high Nile floods in 741-742 AD. The rushing floodwaters could also have overwhelmed the distributary and caused the sediments to become water-laden. In addition, floods often cause rivers to relocate to new courses, and the Canopus distributary may have abandoned its banks following the flooding. It may well be that both disasters took place, and that the resulting decade of physical instability led to the ultimate and final demise of the two cities.

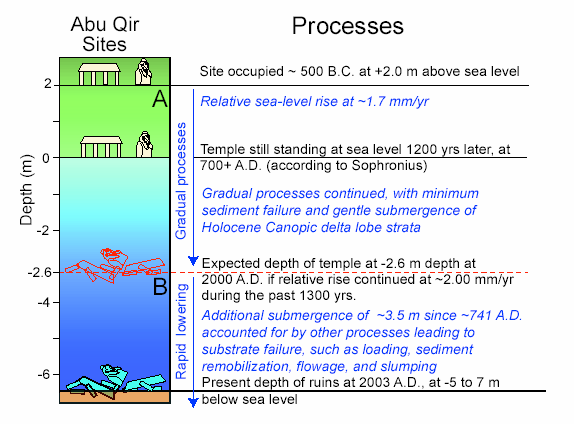

The truth is that these two cities would have eventually disappeared even without one or more natural disasters. The Nile delta - any delta - subsides over time as water is pushed out from between individual sediment grains during compaction. The following time-line shows the likely sequence of events, both gradual and catastrophic, that led to the ultimate demise of Canopus and Herakleion. As you look at the image, think about the future of New Orleans.

Timeline for geologic processes at Abu Qir sites. Source: Submergence of Ancient Greek Cities Off Egypt's Nile Delta — A Cautionary Tale

Let's look at one more example of an amazing piece of history that was lost under the waters of the Mediterranean near the mouth of the Nile. The "slide show" below shows a map of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World (Image 1) and a modern map (Image 2) that shows the Seven Wonders in a more modern configuration.

Remember that the Seven Wonders, which were catalogued in the 5th Century BC by Herodotus, reflect only those portions of the world known to the ancient Greeks. Other remarkable feats of human construction, including the Great Wall of China, were likely unknown to Herodotus.

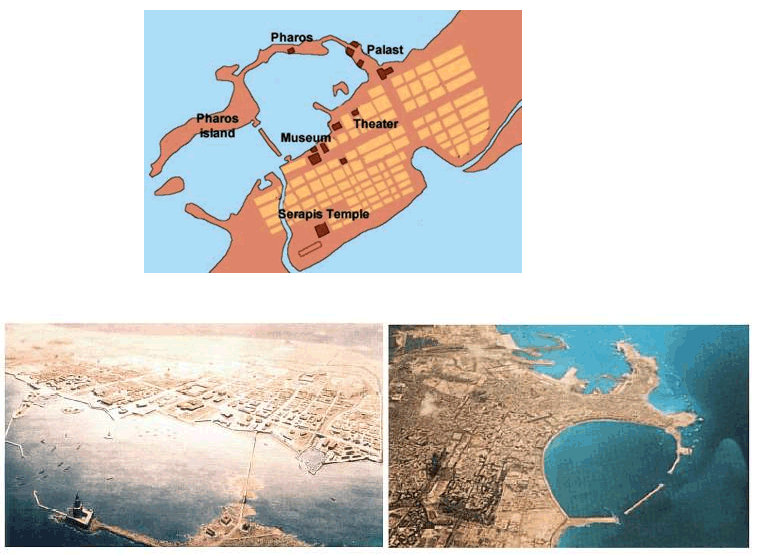

One of the Seven Wonders was the Pharos, or Lighthouse, of Alexandria (see "slideshow" below). The remarkable city of Alexandria (an intellectual and scientific capital of the contemporary world) was founded in 332 BC by the Macedonian conqueror Alexander the Great. Alexander died shortly thereafter (in 323 BC), and the city was completed by Ptolemy Soter, the new ruler of Egypt. Alexandria quickly became a wealthy city as it oversaw activity of trade ships that sailed across the Mediterranean.

Ptolemy authorized construction of the Pharos in 290 BC. It was the first lighthouse in the world, and served as both a symbol of the city as well as a safe guide for shipping in and out of the busy harbor for some 1600 years. When the Lighthouse was completed, about 20 years later, it was the tallest building other than the Great Pyramid. The configuration of the harbor made it dangerous, and so the lighthouse was constructed on Pharos Island (see map below). Several contemporary descriptions of the Pharos - including those by Pliny the Elder - enable us to envision the building as it was in its prime. These descriptions tell how the mirror could reflect light from tens of kilometers away, and how the mirror (perhaps an early telescope) was used to detect enemy ships before they sailed towards the harbor. A statue of Poseidon stood at the top of the tower.

Pharos. Source: http://www.mlahanas.de/Greeks/Pharos.htm

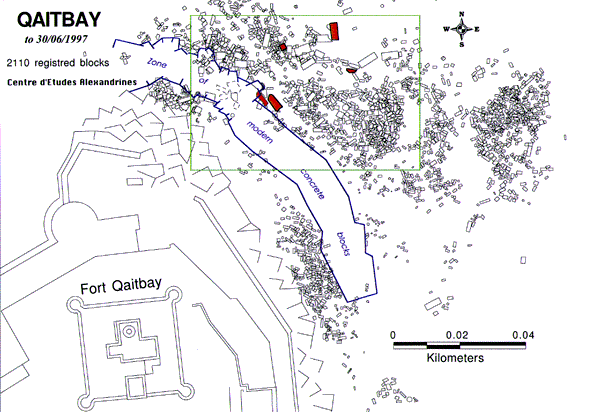

Where is the Pharos now? A series of earthquakes between the 4th and 14th Centuries AD gradually destroyed the lighthouse; its final collapse came in 1326 AD. Some archaeologists believe the ruins of the Pharos lie in the harbor near modern Fort Qaitbey. You can learn about the excavation of the lighthouse at http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/sunken/.

Qaitbay. Source: http://www.culture.gouv.fr/culture/archeosm/archeosom/en/alexandrie6.htm

Note: Please click on the image to see a larger version.